What is Citizen Science?

It can be argued that the original citizen scientists were individuals like Thomas Jefferson, Gilbert White, Charles Darwin, John Burroughs, and Henry David Thoreau, essentially amateurs engaging an interest, indeed a hobby. Thoreau for example documented in great detail the phenology of many species at Walden Pond. [1] Since the history of nature writing is that of individuals who were not scientists, but amateurs, there is some basis to this argument. As a rule, however, science and scientists are impartial. Amateur naturalists tend towards impassioned. The sample sets of information, much like mine, even over a great deal of time would be limited, largely mensurative, more qualitative than quantitative, or simply empirical.

Prior to 1900, there were several collaborative scientific efforts involving amateurs, notably in weather and astronomy.[2] The earliest example of what the Cornell Lab of Ornithology calls PPSR[3] —Public Participation in Scientific Research— and that is still ongoing, is the Audubon Christmas bird count that began in 1900.[4] Indeed, birds have played an important role in the development of both our understanding of and a means of developing a definition for citizen science. That leads inevitably to what may have been the biggest player in citizen science, the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. The term citizen science is attributed to Alan Irwin, a sociologist, but it was Rick Bonney, Director of Education at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology at the time, who is credited with having first applied the term citizen science, in the context of ecological science, as an alternative to amateur science, in 1995.[5] The term citizen science first appeared in the Oxford English Dictionary in 2014.[6] The Cornell Lab of Ornithology currently defines citizen science as “projects in which volunteers pair with scientists to answer real-world questions.”[7]

The evolution of citizen science has not all been smooth sailing. Scientists were resistant to giving citizens a role in data gathering for several reasons. Firstly, there was the pervasive attitude that only trained scientists, certainly not the amateurs that represent American nature writing, could perform the tasks required to produce peer-reviewed publishable science. For amateurs to be able to do such tasks, experimental research would have to be designed in a certain way that “regular” people could accurately gather usable data, and the scientists might need to provide training as well.[8] One of the issues with “usable” data is that scientists gather data to publish, if the data would not lead to publication, then what was the point?[9]

From the time Bonney —and Irwin— first used the term citizen science to describe public participation in scientific research, global internet usage went from less than 1% of the population to almost 50%.[10] That huge expansion of usage coincided with an expansion of the ability to capture and manage data as well as the acceleration of social media usage. That expansion resolved one of the scientific community’s stressors, the issue of questionable data was lessened by volume, effectively a huge sample size. There was still the pressure to publish peer-reviewed results.[11] In part due to increased internet usage and technological advances, volunteer contributions to scientific research tend to consist of collecting data for scientists to analyze and interpret, or the cumbersome but necessary job of analyzing data previously collected by scientists. However, hand-held mobile devices and the popularity of social media also conspired to give many people a voice.[12] And, citizen science is uniquely qualified to respond to the concerns of the citizenry. It is no surprise then that water quality, climate change, phenology, invasive species, species inventories, local environmental issues, and bringing science to children and the general population have moved to the forefront of research efforts.[13]

While many citizen science projects, including some of those listed below, are ongoing and thriving with scientists at the helm, in some ways nature study has come full circle, back in the hands of passionate amateurs who can partner with scientifically-trained professionals. Scientific understanding is being shared peer to peer, amateur to amateur, via social media networks focused on communal knowledge. It seems to me that, the electronic exchange of information has not only enabled citizens, amateur scientists, to provide researchers with a large and quickly obtainable data set, but provided via social media, an opportunity for those amateurs to engage in discourse, citizen scientist to citizen scientist, freeing science from the ivory tower.[14] I feel strongly that the public —the citizenry— must be a driving force in environmentally focused scientific research, both to foster a scientifically literate public and to encourage personal investment in the results.

Below I have included a variety of research venues: governmental, academic, private non-profit, and social network in order to illustrate the breadth of projects that are happening. At the same time, I have chosen to focus on the Hudson Valley and New York, the primary locale of this website.

“For more than 30 years, the Cary Institute has been a global leader in ecosystem science, and the application of that science to environmental policy. Areas of expertise include disease ecology, freshwater and forest health, climate change, urban ecology, and invasive species. We work across ecosystems: forests, rivers, lakes, and cities. The Institute has national standing, local roots in the Hudson Valley, and a global reach with projects on five continents.

Our education program fosters ecosystem literacy among students, teachers, policy makers, and citizens…from Eco-Discovery Camp serving…area students to…Forums for local officials.”

Joshua R. Ginsberg, Ph. D., President

Phenology is the study of the cyclical and seasonal changes, in this case, to plant life.

The Cary Institute for Ecosystem Studies in Millbrook, NY has almost 2000 acres with trails and is open to the public for hiking and exploring annually from April 1 until October 31.

The website has resources for educators, students, and policymakers.

They offer a variety of classes free and open to the public including Friday evening lectures and Sunday morning subject specific walks.

One of many research topics the Cary scientists are working on is a project with Bard College using experimental techniques in selected Dutchess County neighborhoods to control Lyme disease, of which Dutchess has a nationally high incidence, called The Tick Project.

Cary scientists were involved in the development of the Lake Observer app for citizen scientist contribution to data on water quality.

Lake Observer app

The Fern Glen, Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies, July 31, 2016

I must admit that there have been moments when my faith in the NYS DEC have been tested, such as the time —predating cellphone photography and text messaging— that the young man on the phone assured me there were no black bear in Dutchess County east of the Hudson. He attempted to convince me that what I was watching was some sort of dog.

Despite our relationship having gotten off to a rocky start, the NYS DEC has since proven a valuable go to resource. The NYS DEC website has basic information about quite a number of animal and plant species in New York. There is information about known invasive species. At-risk and endangered species are discussed. There is plenty of information regarding regulations, including those specific to hunting and fishing on the site. Details on the various New York watersheds and a variety of citizen science projects are also discussed.

I have found that one of the most valuable ways of getting information from the NYS DEC is to sign up for their email newsletter, DEC Delivers. The information you receive is customizable. Information about hazardous waste collection, hiking trails, search and rescues by forest rangers, health advisories, safety tips, recommendations for places to see wildlife, as well as current citizen science projects such as:

Annual Wildlife Observation Data Collection

Invasive Species Awareness Week, which involved both a water chestnut "pull" and a class called:

Citizen Science: Invasives

Join us to learn more about the emerald ash borer, Asian long-horned beetle and the hemlock woolly adelgid. The program will start with an indoor presentation about the background and biology of these invasive species. Afterward, we will visit a trail to see firsthand the signs and symptoms of an infestation and learn what is being done to manage these pests at Five Rivers.

Great Hudson River Estuary Fish Count

Hudson Estuary Trees for Tribs

WAVE

Water Assessment by Volunteer Evaluators

STEM and the Environment

2016 Living Environment Institute

Five Rivers Environmental Education Center, in Delmar, NY is pleased to offer a three-day Living Environment Institute to introduce the environment to teachers and educators as an ideal platform to teach STEM in the classroom or outdoors.

Pool Owners Sought to Participate in Citizen Science Survey to Identify Asian Longhorned Beetle

Clearly, then, the NYS DEC offers a great many opportunities for both engagement in citizen science projects, many connected to education efforts, and many connected to grant opportunities.

I encourage everyone to check out the DEC website and to sign up for the newsletter.

Our Work: Protecting Wildlife, Inspiring Future Generations

"As in nature, we have strength in numbers. National Wildlife Federation works closely with those who span the social and political spectrum, but who are connected by a common commitment to conservation. Our ability to meet the needs of wildlife is inextricably linked to the amazing individuals, groups, organizations and corporations we call our supporters. Together, we form a pack, leveraging our influence to safeguard America’s wildlife and wild places."

Habitat Certification

Read here about the habitat and garden certification process.

Leafsnap: An Electronic Field Guide

"Leafsnap is a series of electronic field guides being developed by researchers from Columbia University, the University of Maryland, and the Smithsonian Institution. The free mobile apps use visual recognition software to help identify tree species from photographs of their leaves. They contain beautiful high-resolution images of leaves, flowers, fruits, petioles, seeds and bark."

The process for using Leafsnap is very easy. The leaf needs to be placed on a sheet of white paper. The leaf needs to be entirely on the paper. It is possible to use more than one sheet if the leaf is large, but this seems to confuse the system a bit due to scale (I had to find a small Sycamore leaf, above). Using the Snap It! window, simply take a picture. The app will search its database and offer some suggestions. If you can confirm the identity, it will show in your "collection" (see above). It will also populate your map (see above). In addition, your identification and location will contribute to the Leafsnap database.

Leafsnap Dataset

"To promote further research in leaf recognition, we are releasing the Leafsnap dataset, which consists of images of leaves taken from two different sources, as well as their automatically-generated segmentations:

-

23147 Lab images, consisting of high-quality images taken of pressed leaves, from the Smithsonian collection. These images appear in controlled backlit and front-lit versions, with several samples per species.

-

7719 Field images, consisting of "typical" images taken by mobile devices (iPhones mostly) in outdoor environments. These images contain varying amounts of blur, noise, illumination patterns, shadows, etc.

The dataset currently covers all 185 tree species from the Northeastern United States."

Other Items of Interest

Here are some additional links that I found to be of interest and related to the topic.

Citizen Science. org

Home of the Citizen Science Association

"Citizen science is the involvement of the public in scientific research – whether community-driven research or global investigations. The Citizen Science Association unites expertise from educators, scientists, data managers, and others to power citizen science. Join us, and help speed innovation by sharing insights across disciplines."

(In partnership with the Cornell Lab of Ornithology.)

A link to their journal: Citizen Science: Theory and Practice

"Citizenscience.gov is an official government website designed to accelerate the use of crowdsourcing and citizen science across the U.S. government. The site provides a portal to three key assets for federal practitioners: a searchable catalog of federally supported citizen science projects, a toolkit to assist with designing and maintaining projects, and a gateway to a federal community of practice to share best practices."

Photographs by Marc Chappell

A really topnotch, well-curated, well-labelled, and eclectic collection of excellent nature photographs.

Alex T Images

My very good friend Alex's collection of nature photographs, primarily, but not exclusively, of raptors.

The Cornell Lab of Ornithology is as much the fount of citizen science, as well as information on birds and birding as any institution. Its "All About Birds" page alone is worth a look. As soon as I signed up I received an email invitation to take part in the following citizen science projects:

Great Backyard Bird Count -- http://birdcount.org/

Celebrate Urban Birds -- http://celebrateurbanbirds.org/

Project FeederWatch -- http://feederwatch.org/

eBird -- http://eBird.org/

NestWatch -- http://nestwatch.org/

YardMap -- http://yardmap.org/

Below are some thoughts and images about the affiliated Macaulay Library, the Merlin Bird ID app, and the Yardmap project.

The Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology is an amazing collection of animal, mostly bird, audio and video. The entire contains over 160,000 animal sounds and over 50,000 videos. The catalog, which contains more than 148,000 bird calls, is divided into birds, mammals, reptiles, amphibians, arthropods, and fishes.

The collection is free to browse, which would be ideal for a beginning (or even intermediate or expert) birder to familiarize themselves with individual calls, as well as variation by sex and aspects like temperament. Upon signing up, participants receive an email inviting them to participate in citizen science projects (see above). Since many of those projects are bird related, a familiarity with bird calls would definitely be a plus.

In addition, users can request individual or collections of sounds for their own use such as this mammal gallery and this bird gallery. The price varies, based on usage. For example, because this website is an academic project and not for profit, there was no charge for the sounds. I would imagine that for a movie or similar project the price would reflect the for profit nature of the work.

II am a bit partial to the Peterson Birds of NA app, in part because it seems to do a really excellent job coordinating location services with the date, but it also costs $14.99. The Merlin Bird ID app functions in much the same way and is free. It is really simple, in a good way, and seems ideal for a quick identification, especially for beginners.

After choosing Start Bird ID> on the opening screen, the user is prompted to select a location using either location services or by choosing a prior auto-saved location. The user is then taken through the below five screens. I intentionally led the process to American Robin, but have also ended with unresolved results. This app, like the Peterson app, provides bird calls, and the ability to keep track of your results. The information being provided, from the data collected in the eBird -- http://eBird.org/ project.

Support the Cornell Lab:

Give or renew a gift membership

Renew your own membership

Make a donation

I really wasn't familiar with the Yardmap project when I decided to use that concept to demonstrate where I had observed various species here, here, and here. I am not sure everyone will believe me because it is a brilliant concept. But, the brilliance is in the long term idea of an integrated map more so than the mapping of one fragmented habitat, segregated by taxonomical class. That is, of course, the value of YardMap -- http://yardmap.org/ as a citizen science initiative.

I will certainly focus more attention on accurately rendering my property moving forward.

Above is the roughed out version of my property from the Yardmap project. The desktop screen, not shown in its entirety here, wisely taps into social media strategies, by showing recent additions to other members maps on the left, and live member comments on the right.

Above is a reminder/to do list from the Yardmap team. They do an excellent job encouraging participant engagement.

Our Story

"Riverkeeper is a member-supported watchdog organization dedicated to protecting the environmental, recreational and commercial integrity of the Hudson River and its tributaries, and to safeguard the drinking water of nine million New York City and Hudson Valley residents.

For 50 years Riverkeeper has been New York’s clean water advocate. We have helped to establish globally recognized standards for waterway and watershed protection and serve as the model and mentor for the growing Waterkeeper movement that includes over 300 Keeper programs across the country and around the globe."

CITIZEN SCIENCE PARTNER

The icon leads to the App store, the text above the icon will take you to the desktop website.

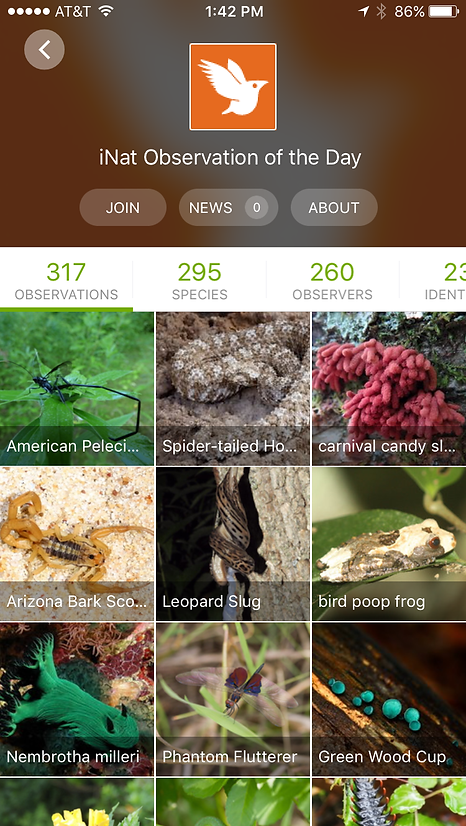

iNaturalist bills itself as "a community for naturalists," and is an example of the way in which mobile technology for citizen science has capitalized on our cultural zeal for social media interaction.

The website suggests a three-step process for the over 300,000 members.

"Record your observations

Share with fellow naturalists

Discuss your findings"

Meanwhile, iNaturalist.org ... "share(s) your findings with scientific data repositories like the Global Biodiversity Information Facility to help scientists find and use your data."

The app allows the user to collect their own observations, categorize their observations by topic as projects, collaborate with others on projects, and view other participant projects, parsed by location if desired. Over 95,00 species have been observed and identified.

I think that the future of citizen science will capitalize on the public's fascination with social media and with interacting with others via electronic media.

Above you can see a couple of screenshots from a feature the app refers to as "Observation of the Day."

Notes

[1] Kayri Havens and Sandra Henderson, “Citizen Science Takes Root.,” American Scientist 101, no. 5 (October 9, 2013): 378.

[2] Janis L. Dickinson and Rick Bonney, Citizen Science. [Electronic Resource] : Public Participation in Environmental Research. (Ithaca : Comstock Pub. Associates, c2012., 2012), 4. http://library.esc.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=cat02823a&AN=ESC.ebr10551825&site=eds-live.

[3] “What Is Citizen Science and PPSR? — Citizen Science Central,” accessed October 18, 2016, http://www.birds.cornell.edu/citscitoolkit/about/defining-citizen-science.

[4] Havens and Henderson, 380.; “Christmas Bird Count,” Audubon, accessed July 24, 2016, http://www.audubon.org/conservation/science/christmas-bird-count.

[5] Akiko Busch, The Incidental Steward: Reflections on Citizen Science (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013), 19.; David Rejeski and James McElfish, “Citizen Science.,” Environmental Forum 33, no. 4 (August 7, 2016): 62.

[6] David Rejeski and James McElfish, “Citizen Science.,” Environmental Forum 33, no. 4 (August 7, 2016): 62.

[7] “Defining Citizen Science — Citizen Science Central,” accessed October 18, 2016, http://www.birds.cornell.edu/citscitoolkit/about/definition.

[8] Kate Mills, “Only ‘Scientists’ Can Do Science,” accessed August 1, 2016, https://www.edge.org/response-detail/25504.; Facebook started in February, 2004.

[9] Dickinson and Bonney, 2.

[10] Rejeski and McElfish, 62.

[11] Dickinson and Bonney, 2.

[12] Rejeski and McElfish, 63.

[13] Dickinson and Bonney, 13.

[14] Stefan Daume and Victor Galaz, “‘Anyone Know What Species This Is?’ – Twitter Conversations as Embryonic Citizen Science Communities.,” PLoS ONE 11, no. 3 (March 11, 2016): 2.